Guest post by Soroush Seifi

Originally published in the Toronto Star, May 21, 2006, D11

My name is Soroush. I was born in Iran 21 years ago and now reside in Toronto. I lived through the eight-year Iran-Iraq war. But this article is not about me. It is about a disturbing trend in education in Muslim countries.

My name is Soroush. I was born in Iran 21 years ago and now reside in Toronto. I lived through the eight-year Iran-Iraq war. But this article is not about me. It is about a disturbing trend in education in Muslim countries.

I hope to draw a correlation between the education system in Iran and the recruitment of angry, young and easily manipulated individuals by terrorist organizations such as Al Qaeda.

The ruins of Ground Zero are proof that we no longer live in an isolated box. The problems of people on one side of the world can bring destruction to people on the other. I say this only to reiterate former secretary of state Colin Powell’s statement in 2004:

To eradicate terrorism, the United States must help… alleviate conditions in the world that enable terrorists to bring in new recruits.

It seems that conditions in the Middle East are not being “alleviated,” as the U.S. administration had planned. Even Republican senators disagree with U.S. President George W. Bush on the war in Iraq.

Meanwhile, the U.N. Department of Economic and Social Affairs’ annual surveys consistently show a lack of freedom of expression, human rights, access to resources, economic stability and technological innovation in societies where most terrorists come from.

So perhaps there are more effective ways than military force to fight terrorism. The failure of American military intervention should prompt us to look at other dimensions of the conflict.

The school system of countries like Iran, where I was educated, is a good place to start.

To be a terrorist, it is not enough to be poor and angry. Otherwise, many more terrorists would originate from places like sub-Saharan Africa, where the rates of poverty are much worse than in Saudi Arabia, the homeland of 15 of the 19 Sept. 11 terrorists. Those terrorists were predominantly from middle-class families.

The more interesting issue is why these individuals were unable to think for themselves and find better ways of showing displeasure than through terrorism. My personal school experience in Iran offers a clue.

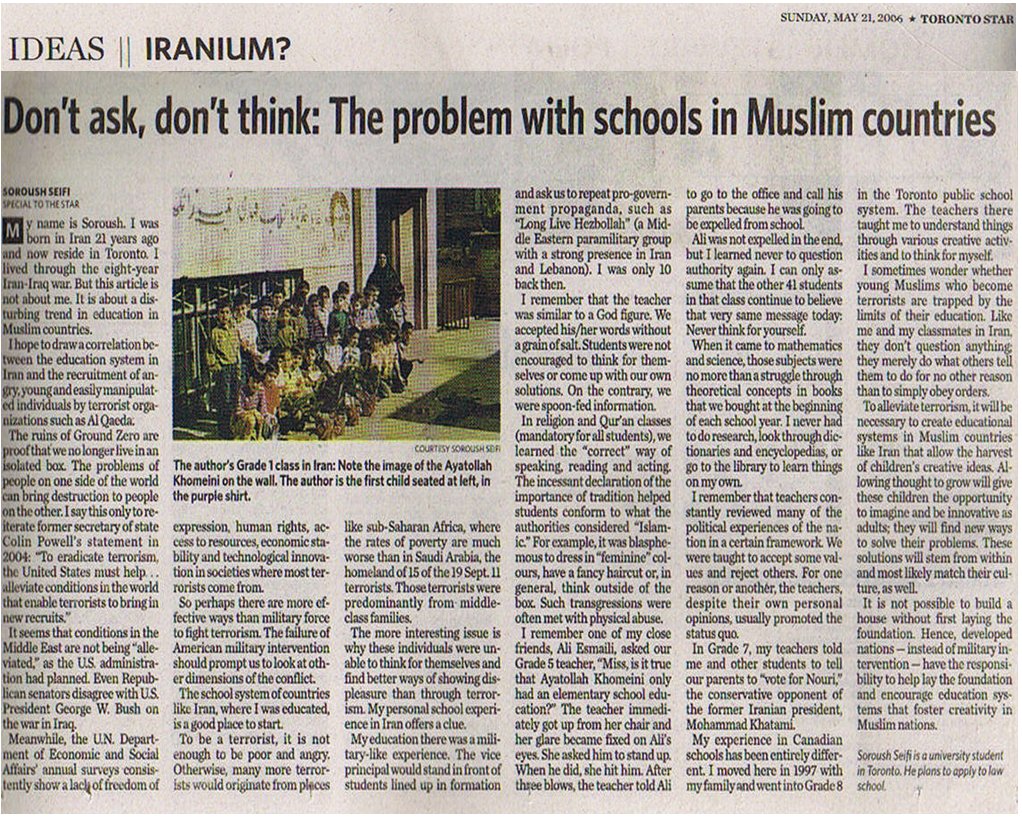

My education there was a military-like experience. The vice principal would stand in front of students lined up in formation and ask us to repeat pro-government propaganda, such as “Long Live Hezbollah” (a Middle Eastern paramilitary group with a strong presence in Iran and Lebanon). I was only 10 back then.

I remember that the teacher was similar to a God figure. We accepted his/her words without a grain of salt. Students were not encouraged to think for themselves or come up with our own solutions. On the contrary, we were spoon-fed information.

In religion and Qur’an classes (mandatory for all students), we learned the “correct” way of speaking, reading and acting. The incessant declaration of the importance of tradition helped students conform to what the authorities considered “Islamic.” For example, it was blasphemous to dress in “feminine” colours, have a fancy haircut or, in general, think outside of the box. Such transgressions were often met with physical abuse.

I remember one of my close friends, Ali Esmaili, asked our Grade 5 teacher,

Miss, is it true that Ayatollah Khomeini only had an elementary school education?

The teacher immediately got up from her chair and her glare became fixed on Ali’s eyes. She asked him to stand up. When he did, she hit him. After three blows, the teacher told Ali to go to the office and call his parents because he was going to be expelled from school.

Ali was not expelled in the end, but I learned never to question authority again. I can only assume that the other 41 students in that class continue to believe that very same message today:

Never think for yourself.

When it came to mathematics and science, those subjects were no more than a struggle through theoretical concepts in books that we bought at the beginning of each school year. I never had to do research, look through dictionaries and encyclopedias, or go to the library to learn things on my own.

I remember that teachers constantly reviewed many of the political experiences of the nation in a certain framework. We were taught to accept some values and reject others. For one reason or another, the teachers, despite their own personal opinions, usually promoted the status quo.

In Grade 7, my teachers told me and other students to tell our parents to “vote for Nouri,” the conservative opponent of the former Iranian president, Mohammad Khatami.

My experience in Canadian schools has been entirely different. I moved here in 1997 with my family and went into Grade 8 in the Toronto public school system. The teachers there taught me to understand things through various creative activities and to think for myself.

I sometimes wonder whether young Muslims who become terrorists are trapped by the limits of their education. Like me and my classmates in Iran, they don’t question anything; they merely do what others tell them to do for no other reason than to simply obey orders.

To alleviate terrorism, it will be necessary to create educational systems in Muslim countries like Iran that allow the harvest of children’s creative ideas. Allowing thought to grow will give these children the opportunity to imagine and be innovative as adults; they will find new ways to solve their problems. These solutions will stem from within and most likely match their culture, as well.

It is not possible to build a house without first laying the foundation. Hence, developed nations – instead of military intervention – have the responsibility to help lay the foundation and encourage education systems that foster creativity in Muslim nations.

Soroush Seifi is a Kinesiologist who graduated in the top 5% of his class during his final year at York University. He was the creator and president of Red Cross Society at York University when he wrote the piece above.

He was recently accepted to Whittier Law School in 2009 on a scholarship, and is currently working before starting law school.

“The ruins of Ground Zero are proof that we no longer live in an isolated box.” – I still don’t understand why people make this claim. Only the extremely ignorant (in the truest sense of the term) would make this claim, as if you had looked at the world before 2001, and after you’d find that not much had changed, except that the West finally felt what every other nation in the world had felt before us. If we had been living in an isolated box, then a handful of men with box-cutters wouldn’t have been able to shake our very foundations.

Westerners just hadn’t been exposed to the nasty, brutish world prior to the 2001 (minus of course embassy bombings, Oklahoma city, naval bombings, and a host of other attacks.)

Also, your title “The problem with schools in Muslim countries” is ridiculously misleading. Here’s a list of the most populous “Muslim countries” (I’m assuming you’re using this phrase to discuss countries with muslim populations…)

Indonesia (most populous “Muslim country”)

Pakistan

India

Bangladesh

Egypt

Nigeria

Iran

Turkey

Algeria

Iraq

Morocco

Saudi Arabi

Sudan

Afghanistan

Ethiopia

Uzbekistan

Yemen

China

Syria

It’s “articles” like these that help contribute to an ignorant world view, and an ingnorant view of Islam(and I could not care less about god or religion), and Muslims.

You talk about isolated experiences in one school in one country and yet brand the article in such a way that an uneducated person would likely come away with a much different view of Muslims, Islam, and the education system in “Muslim countries” than they had going in. You do this with very little evidence, very weak aruments, and very misleading comments.

What is a “Muslim country”? I hate this business of defining a country by the majority religion in the area.

Out of place and too polemical. What’s up with this Law is Cool?

Law is Cool: It’s a guest post, and we like to mix it up a bit. We got an assortment of reactions and responses, which is always a good thing.

I found this article to be thoughtful and interesting – not polemical. However, I get the sense from my readings, from the news, and from my experience with sites like YouTube, that the most dangerous Qaeda recruitment centers are in Europe and Pakistan – and not among the ‘poor’ either.

This article is both misleading and lacks sources of any sort. This individual is speaking from his own point of view of life in the Islamic Republic of Iran.

What the writer forgets to mention or was unaware of was the fact that Saudi has many American and British schools where students must go to. If you are not a Saudi citizen, which is most of the population, one must attain education in these schools. These schools teach the GCSE system which is standardized in Britain and do not get the type of education that the writer discusses.

But I could also give an example of how life in Pakistan was great for me, but that does not help the situation, the facts still remain that the Middle East is oppressed and until the West backs these nations monetarily this will not end.

There is nothing ‘Muslim’ about these nations it is about time that these countries are no longer generalized.

As for the writer’s perspective on the education system in Canada is borderline fairy tale, it seems that the writer has forgotten that stereotypes are still rampant in this society, and that this great educational system still gives an orientalist historical perspective of the ‘other.’

Why is one person giving his point of view such a problem? If that is his experience that is his experience. “Polemical?” that is so laughable.Other people have talked about their experiences with education in the Middle East(Nonie Darwish, Brigette Gabriel). Do people think US pressure for Saudi Arabia to reform their textbooks to be “polemical” or “isolated.” To say that the type of hate-filled education certain populations in the Middle East are exposed to as “isolated” is just indicative of how little people pay attention to world news or pick up a book.

Should we just ignore the teaching of intolerance and support for terrosits groups because it is not politically correct or “polemical..?” when someone brings attention to this fact?

(cont’d)

I thought it was funny that one person commented and said that this post was “lacking in sources.” Seriously? What is the required amount of sources one needs while giving a PERSONAL account of ones experience? True, the article’s title makes it appear like all of Middle Eastern schools have this problem, but when one reads it, it is clear that it is his personal experience. So let’s read it for what is is and not throw it out because he did not cite. If one thinks this is isolated than one should educate themselves further to see if this is the case and draw their own conclusions. Yes there are American schools throughout the Middle East who may not be indoctrinating their students with hate but there are those who do. Calling attention to those American schools doesn’t do anything to address that issue which is where the problem lies.

Originally when I had written this article, it was much longer and more specific talking about standardization of schools from a historical point of view that sucked out all room for critical thinking and creativity in learning. There was referrals to a bunch of good book as well like “what happened to us” by Dr. Zibakalam.

Unfortunately, the Toronto Star editor changed this article, it’s name, and took out much of the specifics leaving in my personal experiences only and creating a really generalized title that can be misleading indeed.

Read it for what it is: a personal experience that may differ person to person.