According to a recent ruling of the SCC, the right to access to government records is now protected by the Charter. In a unanimous 7-0 ruling in Ontario (Public Safety and Security) v. Criminal Lawyer’s Association, [2010] S.C.J. No. 23, the SCC decided that if the information is needed to promote “meaningful public discussion on matters of public interestâ€, Canadians have an access right to that information, guaranteed by s. 2(b) of Charter under the heading “Fundamental Freedoms”.

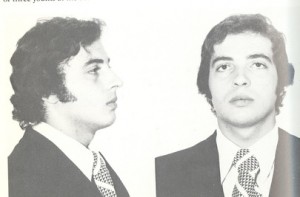

The Criminal Lawyer’s Association (CLA) called this “an epic winâ€, that ensued after a decade-long battle for access to a 300-page review conducted by the OPP with regards to how the Hamilton and Halton police “handled the investigation of the 1983 murder of Toronto mobster Dominic Racco. Mr. Racco was shot and killed on December 1983 and his body was dumped on a Milton rail line. Two Hamilton men, Garaham Court and Dennis Monaghan were charged consequently by Hamilton Police. They had the charges stayed in 1997 after Justice Stephen Glithero of the Ontario Superior Court found evidence of “flagrant and intentional misconduct†by the Crown and Halton and Hamilton police in the process. An investigation by the OPP ensued that resulted in the review but it was not made public despite CLA’s request. The denial of the government to force the OPP to release the review was basically what fuelled the legal action taken by the CLA that was eventually granted the right to appeal by the SCC.

Although, the CLA found the ruling, an epic victory, it was not granted the right to access the information in the OPP review. The SCC, in turn, held that right to access could only be triggered when the information sought “is necessary for meaningful public discussion on matters of public interestâ€. In matters where the release of information may “interfere with the proper functioning of the governmental institution in questionâ€, or where they are shielded by solicitor-client privilege, such rights are not guaranteed to the public.

For one, the SCC held that the review may contain information about the parties that are protected by the solicitor-client privilege. Furthermore, it was decided that CLA has failed to demonstrate that “meaningful public discussion of shortcomings in the investigation and prosecution could not take place without making the OPP report publicâ€. Yet, the Supreme Court sent back the CLA’s request to the information commissioner for a fresh review. Yet, the ruling was described as “a baby step toward recognizing that access to information is a constitutional right†by Paul Schabas of Blake, Cassels & Graydon LLP.

Many countries including UK and US have similar laws implemented in their laws. Sweden, embedded access to information laws in their legislation in 1766 via their Freedom of the Press Act. The British Freedom of Information Act (2000), implemented such rights into the country’s legal system. In Canada, the Access to Information Act grants citizens access to records held by federal bodies and Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act is the legislation that governs matters that come under the scope of the Ontario provincial government. The significance of this “baby-step†is of course in having the access to information right established as constitutional rather than statutory.

Read this article by Dan Michaluk and Paul Broad of Hicks Morley for further analysis of how this case impacts the government institutions.

Photo: Dominic Racco