The Toronto Star, among others, reports that Omar Khadr’s lawyers have launched a suit against the Canadian government to try and force the repatriation of their client.

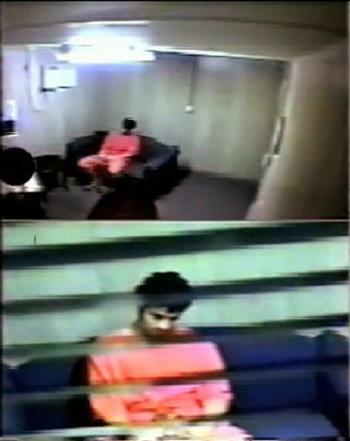

The illegality of Khadr’s detention at Guantanamo Bay is beyond question (and has been covered here extensively). He’s been there for six years, so although he is now an adult, he was legally a minor at the time of his capture. There are also obvious concerns with the "due process" extended to the detainees, concerns about the treatment of all the detainees, and so on.

In May 2008, the Supreme Court ruled in favour of a disclosure application by Khadr’s lawyers in another suit (Canada (Justice) v. Khadr, 2008 SCC 28):

[18] In Hape [R. v. Hape, [2007] 2 S.C.R. 292, 2007 SCC 26], however, the Court stated an important exception to the principle of comity. While not unanimous on all the principles governing extraterritorial application of the Charter, the Court was united on the principle that comity cannot be used to justify Canadian participation in activities of a foreign state or its agents that are contrary to Canada’s international obligations. It was held that the deference required by the principle of comity “ends where clear violations of international law and fundamental human rights begin” (Hape, at paras. 51, 52 and 101, per LeBel J.). The Court further held that in interpreting the scope and application of the Charter, the courts should seek to ensure compliance with Canada’s binding obligations under international law (para. 56, per LeBel J.).

That said, the disclosure case involves the actions of Canadian officials and documents now on Canadian soil. It’s not much of a stretch to apply the Charter to that. On the other hand, this new suit would require the government to act, which would require a finding of a positive obligation inherent in s. 7. That was established–to many people’s great disappointment–in the 2002 Gosselin case:

Section 7 speaks of the right not to be deprived of life, liberty and security of the person, except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice. Nothing in the jurisprudence thus far suggests that s. 7 places a positive obligation on the state to ensure that each person enjoys life, liberty or security of the person. Rather, s. 7 has been interpreted as restricting the state’s ability to deprive people of these. (Gosselin v. Québec (Attorney General), 2002 SCC 84 (CanLII) at para. 81)

The question is not whether the government has a moral or ethical obligation to aid Khadr; clearly it does. It is equally clear that a reasonable reading of obligations under both the Charter and international law would include helping Khadr. That is to say, Canada has every right to take action. However, international law, like the Charter, is loathe to force governments into action. In the absence of political will to act, it is nearly impossible to compel compliance.

It will be interesting to see how this case plays out, but I’m not holding my breath.

In related news, JURIST reports that Khadr’s military lawyer has moved to have the case dismissed on the basis of government misconduct.

Thanks Sarah, good post.

I, like you, am not holding my breath.

You’d better start thinking of yourself.

Let his own lawyer take care of this case.

I wish there was a way in which we can convince Prime Minister Harper to bring Omar Khadr back home so that Omar Khadr receives a fair trial. Khadr was a child when the alleged offences were committed and also any information through abuse or torture should not be permitted. Anyone who is being tortured is going to say anything that the abusers want to hear to save themselves from further abuse or torture. If you google into abuse/torture of detainees you will see for yourselves the extent of abuse that is carried on in Bagram and in Guantanamo Bay.