Part of the International Conflicts series

Part of the International Conflicts series

Introduction

In 2004, the International Criminal Court started to get involved in the situation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, when it was referred to the Prosecutor of the court.

Since then the court has decided to prosecute a single man, Mr. Thomas Lubanga Dyilo, the leader of the “Union Patriotes Congolais†(UPC) and the “Forces Patriotiques pour la Libération du Congo†(FPLC), a rebel group operating in the early 2000s.

The ICC decided to prosecute Mr. Dyilo on three counts, the enlistment of children under the age of 15, the conscription of children under the age of 15, and the active use of children under the age of 15 in hostilities, all considered war crimes within the Rome Statute which established the ICC.

The ICC decided to prosecute Mr. Dyilo on three counts, the enlistment of children under the age of 15, the conscription of children under the age of 15, and the active use of children under the age of 15 in hostilities, all considered war crimes within the Rome Statute which established the ICC.

The Dyilo case gives us an opportunity to discuss the use of international criminal law as a part of conflict management.

- When is it appropriate to use the international criminal court instead of allowing state jurisdictions to take the lead in prosecuting war criminals?

- What are the difficulties of ICC activism in pursuing war criminals?

- Can, and should, international criminal law be used to help deal with conflict and violence?

- Or can it only be applied after a ceasefire or peace treaty has been established?

These are important questions not just for the DRC, but also for the use of the ICC in prosecuting war criminals in general.

What role does war crime prosecution play in dealing with conflict?

The stated purpose of the ICC is to ensure that “crimes of concern to the international community do not go unpunished.†However, much like courts at a national level, the ICC can become, through its work, a force for social change and activism.

Because of the nature of the crimes committed, the ICC’s work becomes part of the process through which a society or state comes to terms with conflict once peace and order has been established. The simple act of sorting out the guilty and innocent is widely seen as a part of the process through which order is created.

Both the ICTY and the ICTR were convened understanding that their work would help the process of restoration and reconciliation through the establishing the facts surrounding the conflict, as well as punishing those who deserve it. In the DRC, the use of prosecution could therefore become a part of national healing and possibly prevent future violence.

However, the default solution within the DRC when dealing with former conflicts and armed groups, has been to ignore the crimes committed by former rebel leaders and instead offer them positions in the national army in order to ensure their loyalty to the government.

The process is known as “mixage†and essentially means that rebel armed groups are subsumed wholesale into the national government.

The logic of this solution appears sound; the government gets a stronger army to deal with further threats and the assurance that former rebel groups are invested into upholding the government. For rebel groups, this allows leaders to keep their position of power.

Overall, it appears that everyone wins. However, this solution does not deal with the root problems, namely why exactly these rebel groups sought to destabilize the government.

As well, and more importantly, those dangerous people who have show that they are capable of committing war crimes are not punished or taken out of society.

Is security really increased when dangerous people not only remain a part of society, but retain positions of power?

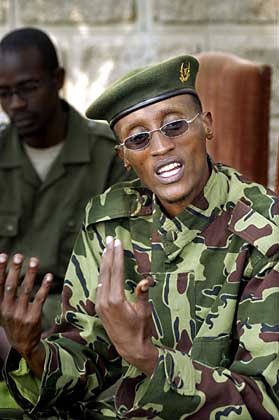

Consider the case of Gen. Nkunda, a former rebel leader turned army commander after his uprising in early 2000. Nkunda has recently started his campaign against the national government using the national army troops under his command.

Consider the case of Gen. Nkunda, a former rebel leader turned army commander after his uprising in early 2000. Nkunda has recently started his campaign against the national government using the national army troops under his command.

Just recently the situation within the eastern part of the conflict has been called a “state of war†as the DRC government engages with troops loyal to Gen. Nkunda.

While ‘mixage’ may be a quick solution that helps the DRC government end serious conflict, it is, unfortunately, not a completely stable solution.

It may not be necessary to try and prosecute all those involved in war crimes, in order to ensure a safe and stable environment, it should be seen as necessary to pursue war crime trials for significant actors in the general war between 1998 and 2003 as well as the during the low-intensity conflicts that have occurred since then.

This ensures that those capable of committing atrocities are taken out of society, and prevents latent anger from brewing amongst victims who may perceive a lack of justice. Often rebel groups in the DRC have formed when ordinary citizens feel abandoned by the government

Why the ICC?

There are several reasons why the ICC should take charge in prosecuting war criminals in the DRC.

In the first case, there is strong evidence that shows that the DRC government has committed war crimes at key points during both the 1998-2003 war, but also in its attempts to quash rebel movements after the war.

Human Rights Watch have accused national soldiers operating in Katanga in 2004 and 2005 of summary executions, torture, arbitrary arrest, and rape, all of which were used as part of a campaign against the Mai Mai insurgency.

It would be inappropriate to simply suggest, without proof, that, in order to protect its integrity, the DRC government would not attempt to prosecute its own national army units.

There is a strong likelihood that, through a variety of means, those people who have committed war crimes while affiliated with the government, will be protected from the full working of the law.

Therefore, by taking the the trial procedures outside of the hands of the government and the national judiciary, every accused, whether a member of the government or of an armed group, will receive an equitable trial and sentence.

Because the ICC is a multilateral third-party, its workings and decisions can be viewed as more legitimate to all parties in the DRC. The ICC has no special interest in the DRC besides ensuring that justice is served, violence and war crimes are punished, and order is established.

Disadvantaged groups may feel more comfortable approaching the ICC as witnesses because the court will be impartial, and therefore not marginalize any group.

Any analysis of the situation in the DRC will not be tainted by a history of regional and ethnic differences.

The limits of the ICC

First, the ICC has been legislated as a “court of last resort.†While this primarily means that war crime cases should be fleshed out at the national level first, it also means that only the most spectacular crimes are meant to be prosecuted at the ICC.

This is reflected in the design of the ICC, which only has 6 judges and is therefore unable to hear a large number of case at once. Overall, the ICC in its current form could not handle the sheer volume of war crime trials that would originate from the DRC in a policy of active prosecution at the international level was established.

Second, the Rome treaty established the principle that at all times the ICC must try and make its decisions in reference to the national laws and court system from which the crime, or criminal, is based.

While the ICC is not prevented from taking an opposing stance to the principles set in the country, there is some ambiguity surrounding how far the ICC can diverge from the state principles.

Would it even be possible to persecute war criminals at the ICC if the DRC refused at accept its decisions?

Despite these obstacles, there is a case to be made that the ICC remains an appropriate actor in the prosecution of war criminals in the DRC.

The Rome treaty provides the ICC the opportunity to take an activist stance in the prosecution of war criminals.

According to Article 13 Section c, the Prosecutor of the ICC is able to initiate an investigation without having to wait for the situation to be referred to them by a member state,

The Court may exercise its jurisdiction with respect to a crime referred to in article 5 in accordance with the provisions of this Statute if:

…(c) The Prosecutor has initiated an investigation in respect of such a crime in accordance with article 15.

The Rome treaty recognizes that the ICC will operate when an issue is ignored by the national judiciary.

Article 18 states that cases presented to the ICC can only be admissible if it is not being pursued by a national court, or at least is not being pursued in good faith by a national court.

2. Within one month of receipt of that notification, a State may inform the Court that it is investigating or has investigated its nationals or others within its jurisdiction with respect to criminal acts which may constitute crimes referred to in article 5 and which relate to the information provided in the notification to States. At the request of that State, the Prosecutor shall defer to the State’s investigation of those persons unless the Pre-Trial Chamber, on the application of the Prosecutor, decides to authorize the investigation.

This Article allows an ICC investigation to be triggered prior to any investigations on the part of the state, rather than waiting for a state to recognize a problem and either choose to investigate or not.

The ICC is therefore given a framework for activism if a situation arises in the world that demands legal action.

There is nothing to prevent the ICC from increasing in size in order to handle an increased volume of trials. The ICC is still in its infancy, and nowhere has it been said that the ICC shall, or even should, remain at its current size.

In its prosecution of Thomas Dyilo, the special prosecutor noted that this would only be the first of many DRC war crime trials that will be heard at the ICC. While the ICC remains relatively small now, it is definitely looking to grow, or at least have the capability to handle a larger volume of trials.

As for the final obstacle, ensuring the consent of the DRC government to prosecute war criminals, this is a tricky issue that will continue to plague the ICC for the rest of its life span.

The ICC will continually be forced to strike a balance between independent activism on the one hand, and respect of state jurisdiction, as well as the consent of member states, on the other.

The end result is strongly tied to the will of the member state to work towards peace and stability within its borders at whatever cost, which will lead to a willingness to purge from itself all those who create violence and instability within the country.

Overall, despite the need for the ICC to maintain its own strong voice in pursuing war criminals, the relationship between the ICC and the DRC should be a partnership.

Both bodies are working towards the same goals, and both are, in the opinion of this writer, necessary for ensuring those goals become reality.