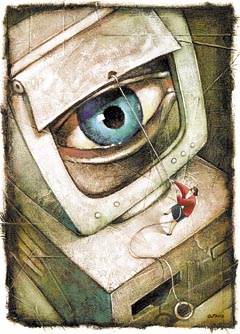

The Ontario Superior Court of Justice has ruled that Canadians have no expectation of privacy in their online identity.

The Ontario Superior Court of Justice has ruled that Canadians have no expectation of privacy in their online identity.

In a St. Thomas-area child porn case, the police asked Bell Canada for a customer’s name and home address based on that customer’s IP address. Bell Canada complied and handed over the information.

The customer’s husband was allegedly using the family computer to search for child porn. He was arrested.

The accused argued that the police search of Bell’s records should have required a warrant. Obtaining his details without a warrant, he claimed, was a violation of his s. 8 Charter right to be free from unreasonable search and seizure.

Justice Lynne Leitch disagreed, writing that:

“One’s name and address or the name and address of your spouse are not biographical information one expects would be kept private from the state.”

Her decision, though it represents an erosion of internet privacy, appears to be well founded. In a moot competition concerning s.8 of the Charter, Omar Ha-Redeye and I argued the exact same point on behalf of the Crown. (Ironically, Justice Leitch was one of the judges of our competition.)

In the appropriately named R. v. Plant, [1993] 3 S.C.R. 281, a marijuana grower sought s. 8 protection for his electricity consumption records. Justice Sopinka held:

… in order for constitutional protection to be extended, the information seized must be of a “personal and confidential” nature. In fostering the underlying values of dignity, integrity and autonomy, it is fitting that s. 8 of the Charter should seek to protect a biographical core of personal information which individuals in a free and democratic society would wish to maintain and control from dissemination to the state. This would include information which tends to reveal intimate details of the lifestyle and personal choices of the individual. The computer records investigated in the case at bar while revealing the pattern of electricity consumption in the residence cannot reasonably be said to reveal intimate details of the appellant’s life since electricity consumption reveals very little about the personal lifestyle or private decisions of the occupant of the residence. [emphasis added]

If you’re interested, see also R. v. Tessling, 2004 SCC 67 at paras. 59-62.

In R. v. A.M., 2008 SCC 19 however, the Supreme Court tempered the “biographical core of personal information” requirement. Binnie J. explained that even where the information sought by police is not aimed at revealing intimate details of the lifestyle of the accused, the analysis does not end there. Simply, the privacy of the contents of a communication is protected if it was reasonably intended by its maker to be private [para 68].

In the present child porn case, Justice Leitch held that the information sought by the police was nothing more than a name and an address. She likened it to information in a telephone book. There were no contents of communications which were worthy of protection.

Ultimately, she found that a customer could not have expected such information to be kept private from the state.

Tech blog Ars Technica criticized the decision:

“Though it’s clear that the ruling in the case (which is still ongoing) was made with good intentions, privacy advocates know what the road to hell is paved with. Critics fear that such a precedent could open the doors to police asking for information on all manner of Internet activities, ranging from the embarrassing to the questionable-but-legal, without judicial oversight.”

Prof. James Stribopoulos, who teaches criminal law and evidence courses at Osgoode, joined the chorus of criticism:

“There is no confidentiality left on the Internet if this ruling stands…”

The reasoning of the judge misses the context of what police are seeking, suggested Mr. Stribopoulos.

“It is not just your name. It is your whole Internet surfing history. Up until now, there was privacy. An IP address is not your name; it is a 10-digit number. A lot more people would be apprehensive if they knew their name was being left everywhere they went.”

This information should require a search warrant by police if there is suspected criminal activity, said Mr. Stribopoulos. Judges are accepting the argument that this is “just your name” because “everyone wants to get at the child abusers,” he said.

The case itself is still ongoing after this Charter ruling.

“In a moot competition concerning s.8 of the Charter, Omar Ha-Redeye and I argued the exact same point on behalf of the Crown. (Ironically, Justice Leitch was one of the judges of our competition.)”

Well, I guess you guys did too good a job.

Well, they seemed to think we did a good job too.

Keep an eye out for my post on unionized employee’s right to privacy on Slaw tomorrow.

This SCJ ruling only confirms what we’ve been saying here. Lawyers’ perception of privacy is illusory. Learning the technology proactively and protecting your identity is probably a better strategy.